A deck watch was used to carry time from the chronometer or chronometers to the place where sextant observations were being made. Ideally, the chronometer would be kept in a place where the motion of the ship was least, but in most vessels of the 20th century, it was to be found under a transparent window beneath the chart table. Deck watches do not have chronometer escapements, which are liable to be upset by sudden, especially rotatory, movements, but they were usually high class “chronometer grade” watches which could be relied upon to keep a steady rate to within a handful of seconds, not as good as a chronometer, but good enough to transfer the time.

A few months ago, I acquired a Soviet era deck watch. Unfortunately, the upper balance staff pivot was broken, but I was able to buy a new staff and, for a trifling NZ$100, a local watch maker replaced it for me (I have since acquired the courage to do this myself). He also offered to clean and oil it for another $2 -300, but I declined this, intending to do the work myself. When collecting it, I asked to see his workshop, where he and his apprentice son work and was interested to see that turning on his lathe depended on his skill with a graver. I gave silent thanks that I had been able to obtain a replacement staff, as to have it made from scratch would have been even more expensive.

After a week or two of running, during which I worked at ascertaining its long-term rate of going, it began to stop after about 20 hours, signifying that something was amiss, perhaps a piece of grit jamming a wheel at the low power end of the train or a problem with the driving force. At this point I suspected a problem with the spring or its barrel, but was later to wonder about the stop work. Overhauling the watch gave me an opportunity to illustrate some of its features.

The watch looks like a large, open faced pocket watch with a centre second hand and is contained in a three part wooden outer case (Figure 1). While this particular version is stem wound and set, earlier versions were had a safety setting pin, and the space for this in the case is visible to the left of the stem.

Figure 1: Deck watch in case.

The watch is named “Polyet” (“Flight”) while earlier versions bore the logo of the First Moscow watch factory. On each side of the 6 is found in Russian “Made in the USSR” (Figure 2). The face is protected by a heavy, flat glass and the bezel and watch case itself is made of chromium plated brass.

Figure 3 shows the placard on the front of the outer case. The first line reads in Russian “First Moscow Watch Factory,” and the second line “Named S M Kirov.” There is a certain irony here, as there is a strong suspicion that Stalin had Kirov murdered in Leningrad in 1934, because of his popularity, and following his death a tractor factory, a military medical academy and other institutions were named in his memory, including, as we have seen, a watch factory. The third line reads “Deck Watch”, while the last line reads GOST, an abbreviation for “State Standard” 17156-71. The outer case is very closely modelled on the outer case of deck watches made by Ulysse Nardin in the 1930s and 40s and, as we will see, so is the movement.

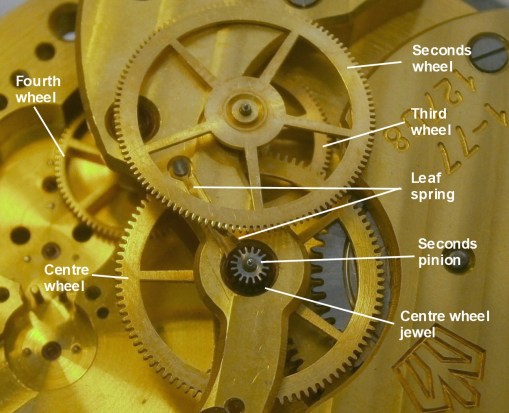

The movement is revealed by removing an outer snap off back and an inner dust cover and Figure 4 shows the movement with the major parts labelled. A Ulysse Nardin Deck watch from about 1940 is shown for comparison in Figure 5. There is a close general similarity, the main differences being that in the Nardin watch the seconds hand, borne on the fourth wheel arbor, is at the more usual six o’clock position and there is a safety setting pin.

Both watches have more than the usual complement of jewels because the balance, the pallets and the escape wheels are all provided with end stones and the train is jewelled to the centre wheel. The extra jewel in the soviet watch is accounted for by the central seconds pinion pivot. The Polyet cocks, plates and wheels are gold plated, with the edges of the cocks carefully bevelled, with a beautiful Geneva wave finish to the cocks. This latter has no function other than to demonstrate the high quality of the time piece, while remaining hidden from all except the watch maker or repairer.The “1-77” indicates that it was made in the first quarter of 1977. The split, bimetallic balance wheel and the lever escapement are conventional as is the train, except in the region of the seconds wheel. Figure 6 shows the area with the cock removed.

Some watches with centre seconds hands have the jewel for the third wheel pivot mounted in the upper train plate or cock, with a projection through the cock on which the seconds wheel is mounted with a press fit. In this watch, the cock is cut away and the jewel is mounted in a separate cock, which is also jewelled for the pivot of the seconds pinion. The latter is held in its jewel by a delicate little leaf spring which presses against the underside of the pinion. Assembling the cock for the seconds wheel and pinion is difficult to manage without the spring slipping from under the pinion and I found the easiest way was to back off the little screw that holds the spring, to assemble the cock, to manoeuvre the spring into its proper place and then to tighten the screw.

The winding and setting mechanism are conventional but the stop work for the winding is a little unusual for a relatively modern watch in that it uses a Geneva mechanism (Figure 7).

The mechanism is accommodated in a figure 8-shaped depression in the lid of the spring barrel. A square on the spring arbor carries a disc with a tongue and the disc is cut away a little each side of the tongue. Another disc having six arms is mounted and rotates about a shouldered screw. Five out of the six arms have concave ends, but the sixth has a convex end. As the spring is wound, the tongue causes the Geneva to rotate up to five times, with the concavity on the end of each arm allowing clearance for it to do so.However, when it reaches the sixth arm, there is no clearance and winding is brought to a halt.

While it might be thought that the purpose of this stop work was to prevent “over winding”, most people with even a slight knowledge of watch and clock mechanisms will know that it is not possible to over wind, though it is of course possible by brute force to break parts of the winding mechanism. Rather, the purpose of the stop work is to prevent the last part of the spring in contact with the spring barrel from coming in to play, as its power is different from that of the rest of the spring and the power delivered to the escapement and balance wheel would vary too much for good time keeping, Of course, the balance spring is adjusted to be isochronous as far as possible, that is to say that its period of swing is the same whatever the amplitude of the spring, but nothing is perfect…

When I got to the spring barrel, I found that the square had partly disintegrated, perhaps because it had been left dead hard and cracked from a sharp corner or because of the application of brute force (not by me!). At any rate, I was obliged to graft in a new square, and after a thorough clean and oiling of the movement, it has since performed as it should.

I hope you have enjoyed reading about this brief exploration of a fine navigational time piece. If so, I am sure you will enjoy “The Mariner’s Chronometer”, obtainable through amazon.com and its associated world-wide branches.

Recent Comments